Once upon a time, there was an implied contract between business and labor: employees supplied their energy and knowledge to build things for which companies paid them. The workers then used their wages to buy products made by business. It was a virtuous circle that made capitalism work for all concerned.

But now, the new technology of automation is increasingly erasing the worker from the equation, and the leaders of government and industry seem not even to notice the coming crisis of capitalism. In fact, the current occupant of the White House has opened the borders to future Democrat voters who will soon find a disappearing market for low-skilled labor because of smart machines.

In the modern factory, the “workers” are technology experts who use computers rather than wrenches.

A Ford automotive assembly line in the 1940s shows human workers building the cars.

Ford is also using artificial intelligence to speed production, and a company video gives a glimpse at the modern factory environment:

A recent article about an upgrade to the Ford automotive assembly robots is a reminder of how central smart machines have become to the company’s production process.

Ford’s ever-smarter robots are speeding up the assembly line, Technologynews.com, May 1, 2021

Ford is adding artificial intelligence to its robotic assembly lines.

In 1913, Henry Ford revolutionized car-making with the first moving assembly line, an innovation that made piecing together new vehicles faster and more efficient. Some hundred years later, Ford is now using artificial intelligence to eke more speed out of today’s manufacturing lines.

At a Ford Transmission Plant in Livonia, Mich., the station where robots help assemble torque converters now includes a system that uses AI to learn from previous attempts how to wiggle the pieces into place most efficiently. Inside a large safety cage, robot arms wheel around grasping circular pieces of metal, each about the diameter of a dinner plate, from a conveyor and slot them together.

Ford uses technology from a startup called Symbio Robotics that looks at the past few hundred attempts to determine which approaches and motions appeared to work best. A computer sitting just outside the cage shows Symbio’s technology sensing and controlling the arms. Toyota and Nissan are using the same tech to improve the efficiency of their production lines.

The technology allows this part of the assembly line to run 15 percent faster, a significant improvement in automotive manufacturing where thin profit margins depend heavily on manufacturing efficiencies.

“I personally think it is going to be something of the future,” says Lon Van Geloven, production manager at the Livonia plant. He says Ford plans to explore whether to use the technology in other factories. Van Geloven says the technology can be used anywhere it’s possible for a computer to learn from feeling how things fit together. “There are plenty of those applications,” he says.

AI is often viewed as a disruptive and transformative technology, but the Livonia torque setup illustrates how AI may creep into industrial processes in gradual and often imperceptible ways.

Automotive manufacturing is already heavily automated, but the robots that help assemble, weld, and paint vehicles are essentially powerful, precise automatons that endlessly repeat the same task but lack any ability to understand or react to their surroundings.

Adding more automation is challenging. The jobs that remain out of reach for machines include tasks like feeding flexible wiring through a car’s dashboard and body. In 2018, Elon Musk blamed Tesla Model 3 production delays on the decision to rely more heavily on automation in manufacturing. (Continues)

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

The year-long Wuhan virus outbreak has been devastating for many economic sectors, but automation has come out a winner because when workers are forced by government into home imprisonment, smart machines can step in to replace the humans. Plus, business owners have developed a larger appreciation of the convenience and dependability of modern robot substitutes.

Below is an NBC report from a few weeks back that includes the new Boston Dynamics robot Stretch, designed for use in a warehouse setting or wherever basic unloading behavior is needed.

Moving boxes around would once have been a perfect job for low-education foreign workers, but now robots can do the task 24/7 with no lunch breaks or paychecks required. There are millions more jobs of all sorts that will be automated in coming years.

So first-world economies won’t be needing any more immigrants with third-world skills because automation is coming on like gangbusters in the near future.

Manufacturers embrace robots, the perfect pandemic worker, NBC News, April 8, 2021

After social distancing measures forced layoffs in labor-intensive factories, manufacturers turned to automation, despite the high cost. Now, they aren’t going back.

Boston Dynamics’ new “Stretch” robot can lift up to 50 pounds at a time and move up to 800 boxes an hour. The company said the pandemic highlighted the growing need for warehouse labor that humans alone can’t provide.

Automation and digitization were already spreading to more factory floors and job sites. Then the pandemic hit.

“It was trial by fire as we went through Covid,” said Mark Bulanda, executive president of automation solutions for Emerson, a manufacturer of systems that automate factory processes.

“Not because of Covid, but because the exodus of people forced the adoption of tech.”

The latest jobs report shows the manufacturing sector grew at its fastest level since the pandemic began, jumping by 50,000 positions. However, there are still about half a million fewer employed manufacturing workers than there were a year ago. The question is how many of those jobs will come back — and how many have been permanently disrupted by digital processes.

Since the pandemic hit, food manufacturers ramped up their automation, allowing facilities to maintain output while social distancing. Factories digitized controls on their machines so they could be remotely operated by workers working from home or another location. New sensors were installed that can flag, or predict, failures, allowing teams of inspectors operating on a schedule to be reduced to an as-needed maintenance crew.

Now, manufacturers are clamoring for even more automated machines so they can cope with spiking demand for their products amid a global recovery and a skilled labor shortage.

Rockwell Automation, a provider of industrial automation solutions, said growth is up 6 percent for the fiscal year and saw sharply increased orders in November and December.

Orders for automated machines are up 30 percent at Eastman Machine Company, a Buffalo, New York-based manufacturer that produces machines that cut specialty materials like carbon fiber and fiberglass, increasingly in demand for cars, aerospace and wind turbines. The backlog for a new device extends to June, their longest in company history.

“When you automate systems, you get greater accuracy,” said CEO Robert Stevenson. “Repeatability is increased. It’s hard to find people who can do that.” (Continues)

Friday’s Washington Times had an eye-catching front-page photo, showing a bench of illegal alien boys all wearing brand new matching clothes — blue polo shirts, pants and slip-on shoes. Apparently the outfits they arrived in weren’t nice enough.

Taxpayers paid for the outfits, thanks to the generous Biden administration, and outgoing dollars for invaders are just beginning. Wait till the hundreds of thousands of kiddies arrive in local schools and need special services for language, healthcare, food and whatever else they might require. We’ve been there, done that during the Obama administration, but now the border is wide open so there are many more foreigners sucking up resources that should go to citizen kids.

Here’s the accompanying article showing the costs charged to unwilling citizens are just beginning:

U.S. taxpayers pay to reunite illegal immigrant families amid border surge, Washington Times, By Stephen Dinan, April 8, 2021

Taxpayers are footing the bill for illegal immigrant parents to collect their children from federal shelters, as the Biden administration tries to speed up the process of getting a record surge of juvenile migrants out of its custody.

Nearly 19,000 unaccompanied children were nabbed jumping the border in March, the Department of Homeland Security revealed Thursday, doubling the number from February and shattering the previous record of about 11,500, set in May 2019.

And while it wasn’t a record, the surge in families attempting to jump the border was also stunning, rising by more than 175% in just one month and suggesting that the unaccompanied children, while drawing the most attention, are not the biggest long-term challenge.

Combined, the families and unaccompanied children accounted for about 72,500 of the 172,331 illegal border encounters Customs and Border Protection recorded in March.

Troy Miller, CBP’s acting commissioner, suggested the situation was under control.

“This is not new,” he said of the surging numbers. “Encounters have continued to increase since April 2020, and our past experiences have helped us be better prepared for the challenges we face this year.”

But analysts said given the current trends, CBP is on track for 1.2 million encounters with illegal border crossers, which would be far above anything the country’s seen since the Bush years. (Continues)

The whole top half of Sunday’s Los Angeles Times featured the victimhood struggles of foreigners whom Biden and previous diversity-admiring administrations have admitted. The headline under the photo reads Migrant Kids Left Waiting for Days, a typical media sob story about illegal aliens.

More alarming in a way is how the article on the right indicates a failure of basic language learning among foreign and/or hispanic students. The piece omits certain helpful information, such as citizenship and time of residence, and instead concentrates on the problems caused by the pandemic.

But when a 13-year-old who has “attended Los Angeles schools since kindergarten” and still cannot speak English, the problem is something other than the virus.

The situations of education failure described are concerning, particularly with what’s coming in a few months — thousands of illiterate foreign children admitted via Biden’s open border will arrive and schools will have to cope. Previous diverse kid dumps have proved expensive to local school districts across the country.

Plus, another strategy of diversity enthusiasts has been to promote a bilingual America which has never been popular among citizens.

A looming catastrophe is about to strike America’s schools. Hopefully the press will report how citizen kids are directly cheated by Biden’s open border. They shouldn’t be forgotten in all the tiresome overdone media concern about foreign children.

The Los Angeles Times supplied hint of what’s coming (reprinted by Yahoo.com, below):

In California, a million English learners are at risk of intractable education loss, by Paloma Esquivel, L.A. Times, April 4, 2021

Aida Vega’s 13-year-old daughter, who has attended Los Angeles schools since kindergarten and is in eighth grade, still struggles to read and write English.

Vega has long pushed for extra help so her child can master the language. Early last year, she felt confident that a breakthrough was at hand — her daughter’s teachers had a plan to start additional tutoring in March.

Then schools closed. Tutoring was canceled, except for a short stint during the fall semester. Vega says her daughter’s schooling became a constant struggle. There are days when Vega has found her in tears next to her computer. In the fall, after teachers said her daughter was failing all of her classes, Vega began taking jobs cleaning homes and offices to pay $45 an hour for a private tutor. But she worries her daughter is still falling behind.

“It’s tough to see the light,” Vega said. “The impact of this time is going to be big. It’s going to be bad.”

More than 1.1 million students in California, nearly 20%, are considered English learners. By almost every measure of academic success — graduation rates, college preparation, dropout rates, state standards — these students rank among the lowest-achieving groups. And that was before pandemic-forced campus closures. One year later, this massive population of students is at great risk of intractable educational loss, experts said.

“It’s an educational pandemic,” said Martha Hernandez, director of Californians Together, a nonprofit that advocates for English learners. “We already had issues of an achievement gap, opportunity gaps, lack of access, lack of equity. Now that’s just exacerbated, and it will be a huge challenge. It will have a big impact for many, many years.”

She and other experts, parents and educators say schools must make immediate and swift interventions to salvage the education of English learners — 80% of whom speak Spanish — including improving distance learning for those families that choose to continue online and extending the school year and school days to allow for additional learning time.

An abundance of reports in California and throughout the country show the dire toll distance learning has taken on these students.

The Los Angeles Unified School District educates about 120,000 English learners, or 20% of its students, and reported that in spring 2020 fewer than half of English learners in middle and high school participated in distance learning each week — a gap of about 20 percentage points compared to students who are proficient in English.

Last month, the district reported that 42% of grades earned by English learners in high school were Ds and Fs, an increase of 10 percentage points from the prior year — greater than any other group except homeless youth. Middle schoolers saw a 12 percentage point increase in Ds and Fs.

And fall interim assessment results indicate that more than 94% of the district’s English learners in middle and high school were not on grade level in reading and math, according to a report this week by the advocacy group Great Public Schools Now, based on district data. (Continues)

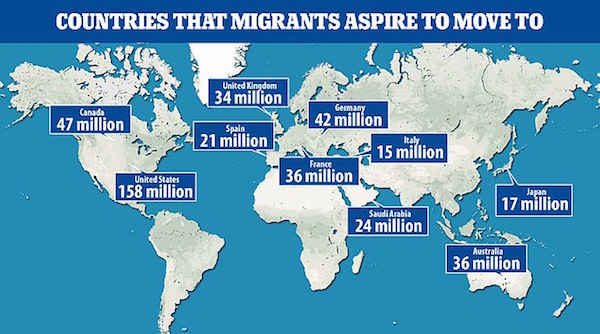

The numbers of foreigners eying Biden’s open border are more than a little scary. A recent Gallup poll found that 42 million persons in Latin America and the Caribbean would like to relocate to the United States.

That number is sobering enough, but foreigners from around the world now travel to the Mexican border to enter the US illegally or by making asylum claims (which were rejected 99 percent of the time under Trump). A migration-themed Reuters article from March 12 noted, “Tijuana also has a large population of Haitian migrants as well as migrants who traveled from Africa.”

So looking only at aliens from the western hemisphere is short-sighted, because they are coming from around the world to grab Biden’s America-destroying freebies.

Below, in 2018 thousands of Indian citizens showed up to claim asylum at the US-Mexico border

A 2018 Gallup poll looked at the worldwide desire to migrate and found that 15 percent of the world’s people — that’s more than 750 million — would like to relocate. One third of sub-Saharan Africans would do so, the highest percentage worldwide. The top choice was the United States, with 158 million desirous of moving here.

Meanwhile, a 2020 Gallup poll reported World Grows Less Accepting of Migrants. So all that imported cultural diversity has not worked out so well in actual practice.

Here’s a blog about the recent Gallup poll:

THE CHAIRMAN’S BLOG: 42 Million Want to Migrate to U.S., Gallup Polls, March 24, 2021

Here are questions every leader should be able to answer regardless of their politics: How many more people are coming to the southern border? And what is the plan?

There are 33 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Roughly 450 million adults live in the region. Gallup asked them if they would like to move to another country permanently if they could.

A whopping 27% said “yes.”

This means roughly 120 million would like to migrate somewhere.

Gallup then asked them where they would like to move.

Of those who want to leave their country permanently, 35% — or 42 million — said they want to go to the United States.

Seekers of citizenship or asylum are watching to determine exactly when and how is the best time to make their move.

In addition to finding a solution for the thousands of migrants currently at the border, let’s include the bigger, harder question — what about all of those who would like to come? What is the message to them?

What is the 10-year plan?

330 million U.S. citizens are wondering. So are 42 million Latin Americans.

America’s newspaper of record had an interesting item earlier this month titled “The Robots Are Coming for Phil in Accounting.” The New York Times apparently meant to remind readers that smart machines aren’t just coming for simple manufacturing jobs, but also for the office gigs that require education.

True, it’s easier to imagine physical robots replacing humans rather than just a little software stuck into a computer, but both threaten the basis of the economy now and into the future.

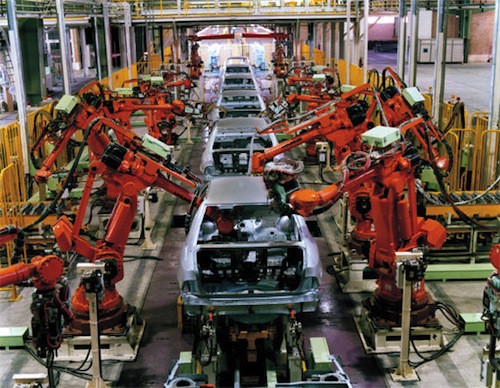

A few decades back, American workers built the nation’s cars:

But now, machines are cheaper and don’t require lunch breaks or expensive health insurance:

The economic shift toward automation and artificial intelligence will only grow. With that trend in mind, America’s future is endangered by the current government’s policy of opening the border and welcoming the world’s poor and uneducated, the number of which continues to grow into the billions.

Furthermore, a 2018 Gallup Poll showed that 158 million persons worldwide would like to relocate to the United States. So Biden’s open borders will have many takers — and there’s no visa required.

Remember:

Automation Makes Immigration Obsolete

The new technology is indeed transforming the world, but Washington does not seem to notice.

The Robots Are Coming for Phil in Accounting, New York Times, March 6, 2021

The robots are coming. Not to kill you with lasers, or beat you in chess, or even to ferry you around town in a driverless Uber.

These robots are here to merge purchase orders into columns J and K of next quarter’s revenue forecast, and transfer customer data from the invoicing software to the Oracle database. They are unassuming software programs with names like “Auxiliobits — DataTable To Json String,” and they are becoming the star employees at many American companies.

Some of these tools are simple apps, downloaded from online stores and installed by corporate I.T. departments, that do the dull-but-critical tasks that someone named Phil in Accounting used to do: reconciling bank statements, approving expense reports, reviewing tax forms. Others are expensive, custom-built software packages, armed with more sophisticated types of artificial intelligence, that are capable of doing the kinds of cognitive work that once required teams of highly-paid humans.

White-collar workers, armed with college degrees and specialized training, once felt relatively safe from automation. But recent advances in A.I. and machine learning have created algorithms capable of outperforming doctors, lawyers and bankers at certain parts of their jobs. And as bots learn to do higher-value tasks, they are climbing the corporate ladder.

The trend — quietly building for years, but accelerating to warp speed since the pandemic — goes by the sleepy moniker “robotic process automation.” And it is transforming workplaces at a pace that few outsiders appreciate. Nearly 8 in 10 corporate executives surveyed by Deloitte last year said they had implemented some form of R.P.A. Another 16 percent said they planned to do so within three years.

Most of this automation is being done by companies you’ve probably never heard of. UiPath, the largest stand-alone automation firm, is valued at $35 billion — roughly the size of eBay — and is slated to go public later this year. Other companies like Automation Anywhere and Blue Prism, which have Fortune 500 companies like Coca-Cola and Walgreens Boots Alliance as clients, are also enjoying breakneck growth, and tech giants like Microsoft have recently introduced their own automation products to get in on the action.

Executives generally spin these bots as being good for everyone, “streamlining operations” while “liberating workers” from mundane and repetitive tasks. But they are also liberating plenty of people from their jobs. Independent experts say that major corporate R.P.A. initiatives have been followed by rounds of layoffs, and that cutting costs, not improving workplace conditions, is usually the driving factor behind the decision to automate.

Craig Le Clair, an analyst with Forrester Research who studies the corporate automation market, said that for executives, much of the appeal of R.P.A. bots is that they are cheap, easy to use and compatible with their existing back-end systems. He said that companies often rely on them to juice short-term profits, rather than embarking on more expensive tech upgrades that might take years to pay for themselves.

“It’s not a moonshot project like a lot of A.I., so companies are doing it like crazy,” Mr. Le Clair said. “With R.P.A., you can build a bot that costs $10,000 a year and take out two to four humans.”

Covid-19 has led some companies to turn to automation to deal with growing demand, closed offices, or budget constraints. But for other companies, the pandemic has provided cover for executives to implement ambitious automation plans they dreamed up long ago.

“Automation is more politically acceptable now,” said Raul Vega, the chief executive of Auxis, a firm that helps companies automate their operations. (Continues)

Reuters reported on March 5 that “U.S. border agents detained nearly 100,000 migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border in February” which means they will soon be released into the United States if they haven’t already.

Many plan on grabbing a job that should go to a US citizen, more the 10 million of whom remain unemployed after a year of the stubborn Wuhan pandemic. The average education of Central American aliens is quite low, with 58 percent of Northern Triangle residents having less than a high school education, according to a recent Peter Navarro report. Those aliens will look for unskilled jobs with the promise to work cheaper than Americans — perhaps in restaurant kitchens.

But technology has been designing a different future for dealing with the pandemic and other labor shortages — robots. Here’s a robot waiter that delivers the chow with no human contact which solves the social distance issue:

In another example, a burger-joint robot is sold as a machine that costs $3/hour and doesn’t call in sick:

The technology keeps expanding. Restaurant kitchens will be getting a makeover that will substantially reduce the need for human workers — and that includes even ultra-cheap illegal aliens eager to please.

A recent industry article observed that “Soon, robots could be integrated into every step of the restaurant supply chain, from the ingredients’ production until the meal arrives at the table”:

New Robots Emerge To Automate Every Stage Of Restaurant Operations, Pymnts.com, February 24, 2021

As the automation of food service progresses, new robots are emerging to tackle a wider range of kitchen tasks. Previously, we saw robots take on salads, bowls and burgers. Now, two new restaurants in Illinois created by Nala Robotics will use automated kitchens to create foods from all around the world, according to Restaurant Hospitality. Cuisines ranging from Malaysian to Mexican to Cajun will be on the menu, with around one hundred meals available to order. The company’s goal is to grow the restaurant through franchising.

The restaurant’s repertoire can increase in just the time it takes to enter a new recipe into the database. Nala Robotics President and Co-founder Ajay Sunkara told Restaurant Hospitality, “if there is a burger joint in New York that has a great following and wants to expand, we can upload that recipe in Naperville, and customers will get the exact same burger.”

While the midwest is getting robot-made cuisine from all around the world, the West Coast is getting its own robot restaurant specializing in Chinese food. The U-Fry Chinese Café, opening this month, will feature foods from five different parts of China prepared by an Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled kitchen, reports The Business Journal. The restaurant’s creator, Tony Pan, has not revealed any specifics about the robots or the software he is using to create this kitchen. (Continues)

Remember:

Automation Makes Immigration Obsolete

The obsession of elites over Race and Racism to the exclusion of almost everything else now is really remarkable. The alleged victimhood of certain tribes is a top narrative every day in the news. The group to blame, the media now asserts, is white people.

The United States was founded and designed by white Protestant men, yet millions of diverse foreigners around the world want to immigrate here. So the narrative is false, but the noise distracts from what the Democrat government is up to — gaining more power.

Tucker Carlson recently discussed the left’s “whiteness” racism and the behavior it requires. Guest JD Vance further observed that “we’re constantly divided against each other, because that’s the way our leaders want it.”

A spare video is here.

TUCKER CARLSON: So you’re not really allowed to notice what’s happening in Seattle or any of our big cities which are collapsing, and people like Robin DiAngelo are charged with making you not notice.

According to Robin DiAngelo, America’s biggest problem has nothing to do with economics. It’s not crime or unemployment. It’s not the mismanagement of the people in charge. The problem with Americans is their DNA.

Now, a sane society would reject that for what it is, open racism, but Robin DiAngelo has gotten richer and more famous. She’s all over television saying the same thing. Your skin color determines whether or not you’re a good person.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

“WHITE FRAGILITY” AUTHOR ROBIN DIANGELO: I’ll never forget asking a group, okay, so what if you could just give us feedback on our inevitable and often unaware racist assumptions and behaviors and I’ll never forget this black man raising his hand and saying it would be revolutionary. And you know, just like — just take that in. I just want all the white people to just take that in.

Revolutionary that we would receive the feedback with grace, reflect and seek to change our behavior. That’s how difficult we are. That’s how big a-holes we are.

JIMMY FALLON, TALK SHOW HOST: Yes.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

CARLSON: Poor Jimmy Fallon. He just wanted to sing songs and do his little comedy thing and yet, he got caught up in this horrible moment and he is going along with it. It is a hostage tape every night.

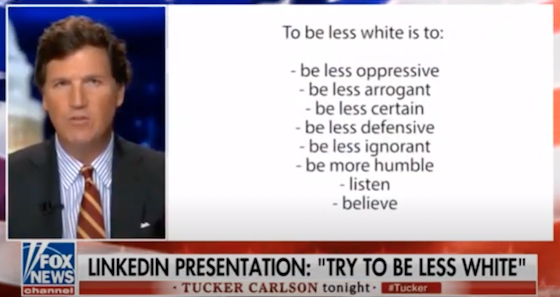

That was last year, by the way, Robin DiAngelo has not gone away. Now, she is delivering video lectures as part of something called “The LinkedIn Learning Series.” And if LinkedIn is behind it, it’s everywhere.

Several major corporations direct employees to the learning platform, which is owned by Microsoft. In wonderful lunatic presentations, DiAngelo notes that quote, “To be less white is to be less oppressive, less arrogant, less defensive, and more humble.” You’re seeing that slide on your screen.

The presentation goes on to urge employees to quote, “Try to be less white.” Again, many corporations are using LinkedIn for training including Coca-Cola, which is run, you won’t be surprised to know, by a white guy.

J.D. Vance is the author of “Hillbilly Elegy.” He joins us tonight. J.D., I have to wonder what effect this kind of stuff is having on our society.

AUTHOR J.D. VANCE: Well, first of all, Tucker, I think it’s ridiculous and frankly, it’s destroying our society.

So you I think about my own family, Tucker, one of the great things that’s happened to me, I think the greatest thing in my life is that I married a woman who wasn’t the same skin color as me and I was able to do that, because I grew up in a country that taught us not to think about each other as members of a racial group. We were taught to think about each other as people.

And what these people are doing by constantly forcing us to focus on the color of our skin is they are destroying an essential part of American heritage that we can judge people based on the content of their character.

They’re doing it, I think, for cynical reasons, but at the end of the day, they’re going to destroy something that’s critical and important and good about this country and we should fight back against it.

CARLSON: I wonder how you can you live in — I mean, we have, cynicism aside, a truly diverse country. There is no majority religion, even barely ethnicity at this point. That’s — I don’t think anyone’s mad about that. But how do you have a country like that if you’re taught by your leaders to hate each other because of your differences? Like how does that work long term?

Continue reading this article

Stephen Miller is a top immigration authority who got Washington experience working for Senator Jeff Sessions and later for President Trump in the White House. Lately he has been appearing on TV discussing the threat posed by the new administration’s border policy.

President Biden’s proposed immigration legislation is beyond extreme in its intent — Miller reports that if passed, it would crush America’s fundamental powers as a nation, namely to control who enters the country. Biden’s borders will melt into nothing as idealized by globalists, transforming citizens into powerless serfs.

Former Trump economist Peter Navarro predicts that more than a million illegal aliens will cross the border in 2021. Obama DHS official Julliette Kayyam has the same numerical estimate.

Most of the foreigners hope to steal American jobs by working extra cheap and avail themselves of generous social services, but there’s nothing to stop enemies from entering among the hordes. Head-choppy jihadists can easily dress like hispanic foreigners to enter for their goal of murdering the hated infidels of the USA.

In addition, more than 10 million Americans are jobless because of the Wuhan virus and shouldn’t be replaced by invasive aliens.

And previously deported foreigners will be invited to re-enter. Amazing, even for Democrats.

Here’s Miller’s appearance on Sunday Morning Futures with Maria Bartiromo:

A spare video is here.

MARIA BARTIROMO: A new border crisis is afoot with congressional Democrats unveiling an ambitious immigration reform bill on Friday that would extend amnesty and citizenship to nearly 20 million illegal immigrants, a population five times the size of Los Angeles. This legislation comes hot on the heels of president Biden’s sweeping executive orders to erase president Trump’s border legacy. Stephen Miller was a senior adviser to President Trump and the architect of the administration’s immigration plan; he joins us this morning.

Stephen it’s great to have you. Let me just point out that you have studied immigration issues for more than a decade. I remember years ago you were a congressional staffer in the House, then you moved over to the Senate. You were studying and working on immigration issues in the Senate before joining President Donald Trump. so give us your expert opinion and assessment of President Biden’s new immigration bill.

STEPHEN MILLER: Thank you, and the reason why I’ve studied immigration so closely is because it’s so fundamental to what it is to be a nation, the right of the people living in a country to decide who enters that country, on what conditions, for how long and how to establish national boundaries and borders. That’s fundamental to what it means to be a country.

The legislation put forward by President Biden and congressional Democrats would fundamentally erase the very essence of America’s nationhood. For the first time I believe in human history, this legislation proposes sending applications to previously deported illegal immigrants and giving them the chance to re-enter the country on a rapid path to citizenship — this is unheard of.

These would be people that ICE officers, at great time and expense, found large numbers of them with criminal records returned to their home countries at taxpayer expense. And now we’re going to have the Secretary of State and Homeland Security mailing applications for readmission and amnesty to previously deported illegal immigrants?

This is madness. Now this is on top of the fact that the current administration has already dismantled border security, canceling President Trump’s historic agreements with Mexico and with the northern triangle countries, restoring catch and release and additionally gutting interior enforcement issuing a memo preventing ICE from removing the vast majority of criminal illegal immigrants that it encounters.

And the last thing I’ll say about that memo is that they have engaged in a fraudulent representation to the court in the Texas litigation because they are claiming this is a resources issue. I know for a fact that ICE has the resources to remove these public safety threats. This is a policy choice disguised falsely to the court and to the country as a resource issue. That is a lie, and it’s a lie that threatens public safety.

BARTIROMO: Wow, and I know that the ICE, Border Patrol men and women are now being told that they have to get authority to make any moves. They need authority from above before detaining anyone. Continue reading this article

To hear professional liberals talk, the United States is a horrible racist place with no redeeming qualities. Seriously, it’s a wonder that anyone would want to relocate here, much less many millions of people around the world.

In fact, a 2018 Gallup poll found that more than 750 million people worldwide want to leave their home nations to relocate elsewhere. Unsurprisingly, the United States was the top choice, with 158 million picking the US.

A report at the time from Tucker Carlson noted a Pew survey that found residents of the receiving nations were not positive toward increasing immigration at all: as Breitbart News accurately headlined Pew: No Majority of Citizens in the World Support Increasing Immigration.

So American citizens who want immigration controlled — not massively increased with open borders as Biden is planning — are normal human beings who want law, order and cultural continuity.

On Monday, Tucker Carlson took up the idea of American racism with Heather MacDonald who recently published a thoughtful article in Newsweek titled If ‘Systemic Racism’ Is Real, Why Does Biden Want To Bring Immigrants Here?.

SPARE AUDIO:

How extreme has the Diversity fixation become in liberal America?

The ideology has certainly gone over the edge when one of the nation’s most far left newspapers, the San Francisco Chronicle, criticizes the current expression of the belief. The occasion was a meeting of a parent committee that advises the city school board where it evaluated the diversity value of a gay man and found him deficient.

The article appeared on the front page of the February 14 edition of the Chron with the headline “To school board, gay dad isn’t diverse enough.”

The members of the committee — three white, three Latina, two black and one Tongan — discussed the issue for two hours of admitting gay dad Seth Brenzel (pictured) to their group. Interestingly, even though Brenzel was present for the entire meeting, he was talked about but never was invited to speak on his own behalf. The members of the committee — three white, three Latina, two black and one Tongan — discussed the issue for two hours of admitting gay dad Seth Brenzel (pictured) to their group. Interestingly, even though Brenzel was present for the entire meeting, he was talked about but never was invited to speak on his own behalf.

More than 200 readers of the Chronicle article commented, with many sounding unimpressed with the behavior of the board members.

The Chronicle article compared the meeting to the TV show Portlandia which portrays “liberalism gone to ludicrous extremes.”

Here’s a clip that shows how Diversity is a strong value in Portlandia:

A Daily Mail article about the school board issue reminded readers that the San Francisco education establishment voted last month to change the names of one-third of the city’s schools, including high schools named after George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. The two presidents are now considered insufficiently virtuous according to modern woke standards.

Here’s the Chronicle article:

San Francisco’s school board is wasting time on ridiculous debates as students remain home, By Heather Knight, San Francisco Chronicle, February 13, 2021

A gay dad volunteers for one of eight open slots on a parent committee that advises the school board. All of the 10 current members are straight moms. Three are white. Three are Latina. Two are Black. One is Tongan. They all want the dad to join them.

The seven school board members talk for two hours about whether the dad brings enough diversity. Yes, he’d be the only man. And the only LGBTQ representative. But he’d be the fourth white person in a district where 15% of students are white.

The gay dad never utters a single word. The board members do not ask the dad a single question before declining to approve him for the committee. They say they’ll consider allowing him to volunteer if he comes back with a slate of more diverse candidates, ideally including an Arab parent, a Native American parent, a Vietnamese parent and a Chinese parent who doesn’t speak English.

Was this an episode of “Portlandia,” the TV satire about liberalism gone to ludicrous extremes? No, it was just another Tuesday night at the San Francisco Board of Education, a group that would provide great entertainment if the consequences weren’t so serious.

Parents teach their children to treat everyone fairly. To not be rude. To listen more than speak. To do research before forming opinions. To not waste other people’s time. To focus on what’s important. To acknowledge mistakes. It’s too bad school board members haven’t learned these lessons over the past dreadful year of distance learning for the more than 52,000 children in their charge.

“What’s wrong with these people? They’re committing political malpractice and educational malpractice seemingly at every meeting,” said Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, a gay man who represents the Castro and said he’s heard repeatedly about gay students in city schools facing bullying and discrimination. “But we don’t want someone queer with an actual seat at the table?”

The Alice B. Toklas LGBTQ Democratic Club on Friday slammed the board for its “misguided fumbling towards a goal of diversity.”

The person who was perhaps the most stunned was Seth Brenzel, the gay dad whose daughter is a fourth-grader at Glen Park Elementary. “At any moment, I expected a commissioner to address me,” he said, “because there I was.”

Knowing his face was beamed live across the city on Zoom, Brenzel kept a neutral expression as the board discussed his race, gender and sexual orientation — and whether they were a worthy mix for the Parent Advisory Council.

“I thought maybe somebody would ask me a question. Like, ‘Hey, Seth, why do you want to be a member of the PAC?’ Or, ‘Hey, Seth, can you tell me about your volunteering in the district?’” he said. “None of that happened.” (Continues)

Earlier this month, Tablet Magazine published an article by Lee Smith titled The 30 Tyrants which compared the triumph of militaristic Sparta over more democratic Athens in ancient Greece to the current efforts of Red China to destroy the culture, economy and world pre-eminence of the United States.

A particularly disturbing point is how America’s elites have lost any loyalty to this country and many look to Beijing for leadership and their future profits. Among the worst of those is the highly corrupt Biden family who are now well placed to accrue more fortunes based on foreign connections built over years.

President Trump recognized the China threat early on and took steps against it. So the ChiCom leadership must be very happy with the 2020 election outcome.

A spare video file is here.

TUCKER CARLSON: Last night, Joe Biden promised to reverse the Trump

administration’s foreign policy on the question of China. According to

Biden, the U.S. will now follow something called the International Rules of

the Road. What does that mean exactly? Well, you can guess what it means.

More subservience to the emerging nation of China.

Most people don’t understand how big this is, or how far back it goes, or

the implications for them. Lee Smith understands. He’s an author and a

journalist. He’s written one of the best pieces of the year on this topic

for Tablet Magazine.

The piece is called “The 30 Tyrants.” You’ll have to stop reading midway through because it’s upsetting. But as you read it, you’ll also know it’s true. So we recommend that you do. He joins us tonight to explain. Lee, thanks so much for coming on.

LEE SMITH: Thanks, Tucker.

CARLSON: And for the mental energy required to connect all these dots in

the piece, and again, I really hope our readers read it for themselves. But

in the meantime, will you summarize your position.

SMITH: Yes, I mean, basically, what I wanted to explain is I wanted to

explain why so many things look crazy. Many things, for instance, that you

cover on your show all the time, for instance, tonight, why people are

coming across — why people are coming across the border in such profound

numbers?

It all looks crazy until you realize there’s a reason it’s going on, and

the reason is, is because the oligarchy that runs this country now is not

primarily loyal to the United States. They do not care about the amount of

damage they do to America. They don’t care about the amount of damage they

do to Americans — that’s part of the system.

Their primary loyalty is to their relationship to the Communist Chinese

Party. That is their center of gravity. It’s the source of their wealth,

privilege and prestige. Continue reading this article

Page 1 of 32212345...102030...»Last »

|

|