But organizing UBI is hardly a small thing. The pricetag will be very high and the emperors of automation might not cotton to being taxed to support the millions of workers that they have disemployed. And wouldn’t free money being handed out be an even bigger magnet to illegal aliens than American jobs?

Of course, when millions of simple jobs are taken over from humans by robots, most immigration will become obsolete and should be ended as an economic adjustment to the automation economy.

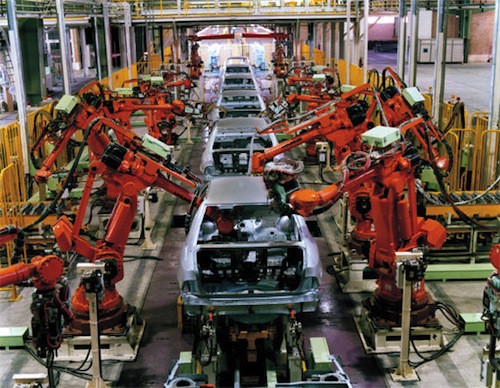

Human workers are impossible to find on some factory floors.

Plus, even if all parties were agreeable to UBI (doubtful), the set-up time might be lengthy because lawyers and politicians will want to be involved. Surely such a major transition away from the economic system of millennia will be difficult.

Following is an article from the optimistic school of thought:

]]>What will life look like when most jobs are automated?, Inverse.com, November 18, 2019

There’s a chance that it might be pretty good.

Experts estimate about a quarter of American jobs could soon be automated. Looking further down the line, we may see a majority of jobs being done by robots. If 60 percent of jobs were to be eliminated, for example, a tremendous amount of people would be out of work, and we’d very likely have to adopt a program like Universal Basic Income (UBI). We don’t yet know how these changes will impact society, but a lot of people are trying to figure out just that.

Martin Ford, a futurist and author of “Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future,” tells Inverse that a majority of jobs could be automated or mostly automated within 20 years or so.

“I think a very large number of jobs are going to be impacted — automated or deskilled. Eventually, it might be a majority,” Ford says.

Ford says just 20 percent of jobs disappearing would have a “staggering impact” on society and the economy. He says the jobs that will be safest, in terms of automation, will be the ones that require some level of creativity.

“The other areas are those things that require unique human qualities like empathy or building sophisticated human relationships with other people,” Fox says. That might include a job where you have relationships with clients, like in sales, or a job where you’re caring for others, he says.

Richard Baldwin, a professor of international economics at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, tells Inverse that jobs that aren’t completely automated will still be affected by automation.

“Almost all occupations will still require some people to do the tasks that can’t be automated or offshored,” Baldwin says. He believes jobs that require human skills like empathy, motivating people, dealing with unexpected situations, curiosity, innovation, ethics will not be automated.

There are also simply jobs that won’t be automated for a long time because it will take so long for the technology to develop, Ford says. He thinks it would take a robot “like C-3PO” to replace an electrician, for example.

Once there are fewer jobs, and some kind of program like UBI that is keeping people financially stable, many believe we’ll simply have more time to do the things we want to do that don’t necessarily earn us much or any money. Presidential candidate Andrew Yang says on his campaign website that UBI will “enable all Americans to pay their bills, educate themselves, start businesses, be more creative, stay healthy, relocate for work, spend time with their children, take care of loved ones, and have a real stake in the future.” (Continues)

The formula is simple: when a machine become less expensive than a worker, [...]]]>

The formula is simple: when a machine become less expensive than a worker, then the human will go. And unlike the Great Depression, the jobs won’t come back.

Among the first jobs to go are the low-skilled sort, the employment that illegal border crossers count on getting in America. It’s likely that automation-caused unemployment would be higher without President Trump’s economic leadership.

Andrew Yang was interviewed yesterday on CBS Sunday Morning (the show made famous by Charles Kuralt and his nostalgic patriotism seen on the nation’s backroads).

Candidate Yang mentioned in his CBS interview about how automation has already had an electoral effect: “We automated away four million manufacturing jobs in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Iowa, all the swing states that Donald Trump needed to win, and did win.”

That job loss is an important point and a reminder that we are already on the big automation highway with no off-ramp.

One criticism of Yang is that he went rather quickly to his universal basic income plan without explaining the need more thoroughly, although it seems public concern about automation job loss is increasing.

Still, if the billions of poor on earth hear that America is handing out free money to everyone, more serious immigration enforcement is needed.

Hopefully the Democrat debate on Tuesday will give Yang more time to talk, which he has not gotten so far.

]]>Andrew Yang on creating a “trickle-up” economy, CBS News, October 13, 2019

In a park in Los Angeles last month, thousands gathered to hear the Democrat perhaps least likely to be running for president. “I am the ideal candidate for that job, because the opposite of Donald Trump is an Asian man who likes math,” said Andrew Yang.

In Yang’s world, MATH stands for “Make America Think Harder,” and Yang is mostly thinking about dire economic times ahead.

[. . .]

Andrew Yang, in fact, calls himself an entrepreneur. His parents immigrated from Taiwan: His father, a physicist, and his mother, with a master’s in math and statistics. Yang grew up in Schenectady, New York. His first big success was running a college test-prep company, and then he founded Venture for America, a non-profit that helps train entrepreneurs in struggling cities.

He thinks jobs – or rather, the loss of them – are why Donald Trump won the presidency.

“The numbers tell a very clear story,” he said. “We automated away four million manufacturing jobs in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Iowa, all the swing states that Donald Trump needed to win, and did win.”

And Yang believes robots and artificial intelligence will accelerate the loss of all kinds of jobs. “Now, what we did to those jobs, we’re doing to the retail jobs, the call center jobs, the fast food jobs, the truck driving jobs, and on and on through the economy,” he said.

Thompson met Yang along the campaign trail, as he took a break for some tea (“Duke of Earl Gray”), and then discovered a foosball table, where he naturally talked about economic theory, and another of his big ideas: reforming how we calculate Gross Domestic Product, or GDP.

“If you want to see how out-of-whack GDP is, all you have to do is look at my family,” Yang said. “My wife is at home with our two boys, one of whom is autistic. And what is her work every day, included at in GDP? Zero. And we know that her work is among the most important work being done for our society.” (Continues)

As a result, the lesser known candidates need to make a splash so people will remember them.

Today’s [...]]]>

As a result, the lesser known candidates need to make a splash so people will remember them.

Today’s example is entrepreneur Andrew Yang, who entered the fray a year ago with a New York Times article introducing him as a tech Cassandra with the headline, His 2020 Campaign Message: The Robots Are Coming.

That approach may have been too gloomy at a time when the jobs economy had been booming, so he is back with an offer of free money — a sure-fire attention getter.

When Fox News host Pete Hegseth asked his guest on Sunday what was up with the cash giveaway, Yang answered, “In my mind, the reason why Donald Trump is our president today is that we automated away 4 million manufacturing jobs in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa, and now we’re about to do the same thing to millions of jobs in retail, call centers, truck drivers, fast food and on and on through the economy. And this message is resounding loud and clear when I talk to Americans in early states around the country.”

Hegseth criticized the idea, but actual experts contemplating the coming automated society have also suggested the strategy of Universal Basic Income. Martin Ford discussed the UBI concept in his influential book Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. He also presented a TED Talk on the topic, viewable here.

In fact many tech experts have rolled out serious predictions that should be considered by our political leaders in Washington. Here is my growing list of warnings: Oxford researchers forecast in 2013 that nearly half of American jobs were vulnerable to machine or software replacement within 20 years. Rice University computer scientist Moshe Vardi believes that in 30 years humans will become largely obsolete, and world joblessness will reach 50 percent. The Gartner tech advising company believes that one-third of jobs will be done by machines by 2025. The consultancy firm PwC published a report last year that forecast robots could take 38 percent of US jobs by 2030. In November 2017, the McKinsey Global Institute reported that automation “could displace up to 800 million workers — 30 percent of the global workforce — by 2030.” Forrester Research estimates that robots and artificial intelligence could eliminate nearly 25 million jobs in the United States over the next decade, but it should create nearly 15 million positions, resulting in a loss of 10 million US jobs. Kai-Fu Lee, the venture capitalist and author of AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, forecast on CBS’ Sixty Minutes about automation and artificial intelligence: “in 15 years, that’s going to displace about 40 percent of the jobs in the world.” A February 2018 paper from Bain & Company, Labor 2030, predicted, “By the end of the 2020s, automation may eliminate 20% to 25% of current jobs.”

Certainly, it is insane for America to continue admitting low-skilled foreigners from peasant economies when machines will be replacing them in a few years. It was disappointing to hear President Trump remark recently that he wanted “more people coming into our country” — a policy which won’t help citizen wages rise and does not recognize the technological train wreck coming our way.

Remember:

]]>Automation Makes Immigration Obsolete

That level of permanent [...]]]>

That level of permanent unemployment sounds like a good argument for ending immigration as an obsolete policy.

In the latter segment of the talk, Ford makes the case for a universal basic income to make the robot revolution more equitable.

]]>MARTIN FORD: I’m going to begin with a scary question: Are we headed toward a future without jobs? The remarkable progress that we’re seeing in technologies like self-driving cars has led to an explosion of interest in this question, but because it’s something that’s been asked so many times in the past, maybe what we should really be asking is whether this time is really different. The fear that automation might displace workers and potentially lead to lots of unemployment goes back at a minimum 200 years to the Luddite revolts in England. And since then, this concern has come up again and again.

00:47

I’m going to guess that most of you have probably never heard of the Triple Revolution report, but this was a very prominent report. It was put together by a brilliant group of people — it actually included two Nobel laureates — and this report was presented to the President of the United States, and it argued that the US was on the brink of economic and social upheaval because industrial automation was going to put millions of people out of work. Now, that report was delivered to President Lyndon Johnson in March of 1964. So that’s now over 50 years, and, of course, that hasn’t really happened. And that’s been the story again and again.01:26

This alarm has been raised repeatedly, but it’s always been a false alarm. And because it’s been a false alarm, it’s led to a very conventional way of thinking about this. And that says essentially that yes, technology may devastate entire industries. It may wipe out whole occupations and types of work. But at the same time, of course, progress is going to lead to entirely new things. So there will be new industries that will arise in the future, and those industries, of course, will have to hire people. There’ll be new kinds of work that will appear,and those might be things that today we can’t really even imagine. And that has been the story so far, and it’s been a positive story.02:03

It turns out that the new jobs that have been created have generally been a lot better than the old ones. They have, for example, been more engaging.They’ve been in safer, more comfortable work environments, and, of course, they’ve paid more. So it has been a positive story. That’s the way things have played out so far. But there is one particular class of worker for whom the story has been quite different. For these workers, technology has completely decimated their work, and it really hasn’t created any new opportunities at all.And these workers, of course, are horses.02:38

(Laughter)02:40

So I can ask a very provocative question: Is it possible that at some point in the future, a significant fraction of the human workforce is going to be made redundant in the way that horses were? Now, you might have a very visceral, reflexive reaction to that. You might say, “That’s absurd. How can you possibly compare human beings to horses?” Horses, of course, are very limited, and when cars and trucks and tractors came along, horses really had nowhere else to turn. People, on the other hand, are intelligent; we can learn, we can adapt.And in theory, that ought to mean that we can always find something new to do, and that we can always remain relevant to the future economy.03:21

But here’s the really critical thing to understand. The machines that will threaten workers in the future are really nothing like those cars and trucks and tractors that displaced horses. The future is going to be full of thinking, learning, adapting machines. And what that really means is that technology is finally beginning to encroach on that fundamental human capability — the thing that makes us so different from horses, and the very thing that, so far, has allowed us to stay ahead of the march of progress and remain relevant, and, in fact, indispensable to the economy. So what is it that is really so differentabout today’s information technology relative to what we’ve seen in the past? I would point to three fundamental things.04:07

The first thing is that we have seen this ongoing process of exponential acceleration. I know you all know about Moore’s law, but in fact, it’s more broad-based than that; it extends in many cases, for example, to software, it extends to communications, bandwidth and so forth. But the really key thing to understand is that this acceleration has now been going on for a really long time. In fact, it’s been going on for decades. If you measure from the late 1950s, when the first integrated circuits were fabricated, we’ve seen something on the order of 30 doublings in computational power since then.That’s just an extraordinary number of times to double any quantity, and what it really means is that we’re now at a point where we’re going to see just an extraordinary amount of absolute progress, and, of course, things are going to continue to also accelerate from this point. So as we look forward to the coming years and decades, I think that means that we’re going to see thingsthat we’re really not prepared for. We’re going to see things that astonish us.05:06

The second key thing is that the machines are, in a limited sense, beginning to think. And by this, I don’t mean human-level AI, or science fiction artificial intelligence; I simply mean that machines and algorithms are making decisions.They’re solving problems, and most importantly, they’re learning. In fact, if there’s one technology that is truly central to this and has really become the driving force behind this, it’s machine learning, which is just becoming this incredibly powerful, disruptive, scalable technology.05:39

One of the best examples I’ve seen of that recently was what Google’s DeepMind division was able to do with its AlphaGo system. Now, this is the system that was able to beat the best player in the world at the ancient game of Go. Now, at least to me, there are two things that really stand out about the game of Go. One is that as you’re playing the game, the number of configurations that the board can be in is essentially infinite. There are actually more possibilities than there are atoms in the universe. So what that means is,you’re never going to be able to build a computer to win at the game of Go the way chess was approached, for example, which is basically to throw brute-force computational power at it. So clearly, a much more sophisticated, thinking-like approach is needed. The second thing that really stands out is that, if you talk to one of the championship Go players, this person cannot necessarily even really articulate what exactly it is they’re thinking about as they play the game. It’s often something that’s very intuitive, it’s almost just like a feeling about which move they should make.06:42

So given those two qualities, I would say that playing Go at a world champion level really ought to be something that’s safe from automation, and the fact that it isn’t should really raise a cautionary flag for us. And the reason is that we tend to draw a very distinct line, and on one side of that line are all the jobs and tasks that we perceive as being on some level fundamentally routine and repetitive and predictable. And we know that these jobs might be in different industries, they might be in different occupations and at different skill levels,but because they are innately predictable, we know they’re probably at some point going to be susceptible to machine learning, and therefore, to automation. And make no mistake — that’s a lot of jobs. That’s probably something on the order of roughly half the jobs in the economy.07:30

But then on the other side of that line, we have all the jobs that require some capability that we perceive as being uniquely human, and these are the jobs that we think are safe. Now, based on what I know about the game of Go, I would’ve guessed that it really ought to be on the safe side of that line. But the fact that it isn’t, and that Google solved this problem, suggests that that line is going to be very dynamic. It’s going to shift, and it’s going to shift in a way that consumes more and more jobs and tasks that we currently perceive as being safe from automation.08:01

The other key thing to understand is that this is by no means just about low-wage jobs or blue-collar jobs, or jobs and tasks done by people that have relatively low levels of education. There’s lots of evidence to show that these technologies are rapidly climbing the skills ladder. So we already see an impact on professional jobs — tasks done by people like accountants, financial analysts, journalists, lawyers, radiologists and so forth. So a lot of the assumptions that we make about the kind of occupations and tasks and jobsthat are going to be threatened by automation in the future are very likely to be challenged going forward.08:40

So as we put these trends together, I think what it shows is that we could very well end up in a future with significant unemployment. Or at a minimum, we could face lots of underemployment or stagnant wages, maybe even declining wages. And, of course, soaring levels of inequality. All of that, of course, is going to put a terrific amount of stress on the fabric of society. But beyond that, there’s also a fundamental economic problem, and that arises because jobs are currently the primary mechanism that distributes income, and therefore purchasing power, to all the consumers that buy the products and services we’re producing.09:22

In order to have a vibrant market economy, you’ve got to have lots and lots of consumers that are really capable of buying the products and services that are being produced. If you don’t have that, then you run the risk of economic stagnation, or maybe even a declining economic spiral, as there simply aren’t enough customers out there to buy the products and services being produced.09:44

It’s really important to realize that all of us as individuals rely on access to that market economy in order to be successful. You can visualize that by thinking in terms of one really exceptional person. Imagine for a moment you take, say, Steve Jobs, and you drop him on an island all by himself. On that island, he’s going to be running around, gathering coconuts just like anyone else. He’s really not going to be anything special, and the reason, of course, is that there is no market for him to scale his incredible talents across. So access to this market is really critical to us as individuals, and also to the entire system in terms of it being sustainable.10:25

So the question then becomes: What exactly could we do about this? And I think you can view this through a very utopian framework. You can imagine a future where we all have to work less, we have more time for leisure, more time to spend with our families, more time to do things that we find genuinely rewarding and so forth. And I think that’s a terrific vision. That’s something that we should absolutely strive to move toward. But at the same time, I think we have to be realistic, and we have to realize that we’re very likely to face a significant income distribution problem. A lot of people are likely to be left behind. And I think that in order to solve that problem, we’re ultimately going to have to find a way to decouple incomes from traditional work. And the best, more straightforward way I know to do that is some kind of a guaranteed income or universal basic income.11:16

Now, basic income is becoming a very important idea. It’s getting a lot of traction and attention, there are a lot of important pilot projects and experiments going on throughout the world. My own view is that a basic income is not a panacea; it’s not necessarily a plug-and-play solution, but rather, it’s a place to start. It’s an idea that we can build on and refine. For example, one thing that I have written quite a lot about is the possibility of incorporating explicit incentives into a basic income. To illustrate that, imagine that you are a struggling high school student. Imagine that you are at risk of dropping out of school. And yet, suppose you know that at some point in the future, no matter what, you’re going to get the same basic income as everyone else. Now, to my mind, that creates a very perverse incentive for you to simply give up and drop out of school.12:06

So I would say, let’s not structure things that way. Instead, let’s pay people who graduate from high school somewhat more than those who simply drop out. And we can take that idea of building incentives into a basic income, and maybe extend it to other areas. For example, we might create an incentive to work in the community to help others, or perhaps to do positive things for the environment, and so forth. So by incorporating incentives into a basic income,we might actually improve it, and also, perhaps, take at least a couple of stepstowards solving another problem that I think we’re quite possibly going to face in the future, and that is, how do we all find meaning and fulfillment, and how do we occupy our time in a world where perhaps there’s less demand for traditional work?12:54

So by extending and refining a basic income, I think we can make it look better, and we can also, perhaps, make it more politically and socially acceptable and feasible — and, of course, by doing that, we increase the odds that it will actually come to be.13:11

I think one of the most fundamental, almost instinctive objections that many of us have to the idea of a basic income, or really to any significant expansion of the safety net, is this fear that we’re going to end up with too many peopleriding in the economic cart, and not enough people pulling that cart. And yet, really, the whole point I’m making here, of course, is that in the future,machines are increasingly going to be capable of pulling that cart for us. That should give us more options for the way we structure our society and our economy, And I think eventually, it’s going to go beyond simply being an option, and it’s going to become an imperative. The reason, of course, is that all of this is going to put such a degree of stress on our society, and also because jobs are that mechanism that gets purchasing power to consumers so they can then drive the economy. If, in fact, that mechanism begins to erode in the future, then we’re going to need to replace it with something else or we’re going to face the risk that our whole system simply may not be sustainable.14:12

But the bottom line here is that I really think that solving these problems, and especially finding a way to build a future economy that works for everyone, at every level of our society, is going to be one of the most important challenges that we all face in the coming years and decades.14:30

Thank you very much.

But universal income is a hard sell, with so many ways it [...]]]>

But universal income is a hard sell, with so many ways it could go wrong — like seven billion potential moochers worldwide. The social effect is likely to be huge because many people won’t easily adjust to having nothing but free time and no job to define their identity.

Also, it’s difficult to be convincing about the need for a fix when the threat is not laid out clearly, even when the existing expert warnings are substantial. Oxford researchers forecast in 2013 that nearly half of American jobs were vulnerable to machine or software replacement within 20 years. Rice University computer scientist Moshe Vardi believes that in 30 years humans will become largely obsolete, and world joblessness will reach 50 percent. The Gartner tech advising company believes that one-third of jobs will be done by machines by 2025. Forrester Research Inc. has a more optimistic view, that there will be a net job loss of 7 percent by 2025 from automation.

Below, human workers can be hard to find in automotive factories, which are now largely automated.

I understand that less than three minutes is not a lot of time to discuss the complete erasure of the market system of pay for labor, but explaining the extent of the problem here takes up only a few seconds. And of course there is no mention that the automated future will need Zero immigrant workers.

The following article is a knock-off of the video report:

]]>Universal Basic Income: A concept that would mean a paycheck, even if you don’t have a job, Fox 6, June 29, 2017

MILWAUKEE — How does this sound? You get a paycheck each month, even if you don’t have a job! It’s called Universal Basic Income, and it’s growing in popularity as a concept for the not-too-distance future.

The Senate rejected the idea way back in 1970, but the ravages of the digital age are causing many to revisit the concept of a Universal Basic Income.

“We need new jobs, good jobs, with rising incomes,” Hillary Clinton said during the 2016 presidential campaign.

“We have to do a much better job at keeping our jobs,” then-candidate Donald Trump said during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Yet during the three presidential debates, the word “automation” never came up. With credible projections now forecasting that our growing use of robots, self-driving vehicles and other automated machinery will eliminate 40 percent of all jobs in the United States by 2030, futurists, labor market analysts and leading CEOs have begun asking “what will become of all those workers displaced by technology?”

“Now it’s time for our generation to define a new social contract,” Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook founder said.

At Harvard in May, Zuckerberg endorsed the concept of a Universal Basic Income — a guaranteed wage for some or all Americans, to be means-tested or limited to the losers in the emerging new economy of the digital age.

“We should explore ideas like Universal Basic Income to make sure everyone has a cushion to try new ideas,” Zuckerberg said.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk told a forum in Dubai 12 to 15 percent of the human workforce will be rendered obsolete within 20 years.

“This is going to be a massive social challenge, and I think ultimately we will have to have some kind of Universal Basic Income. I don’t think we’re going to have a choice,” Musk said.

The idea has been tested on a small scale in Canada, Finland and the Netherlands — with results disputed.

Some studies showed work ethic and wellness among recipients actually improved.

It was proposed in the United States back in 1970, when liberal adviser Daniel Patrick Moynihan persuaded Republican President Richard Nixon to unveil the “Family Assistance Plan,” which died in the Senate. Critics argue a guaranteed income is not only socialist but defeatist.

“The challenge, I think, for public policy is to make sure that workers are equipped to work in the new kinds of jobs that the economy is creating, to make sure that workers are supported in aspirations to work,” Michael Strain, American Enterprise Institute.

All of this is a long time coming.

Woody Allen’s standup routine in the 60s includes a joke about his father losing his job after 12 years at the same company to a gadget that could do everything his father could, only better. The depressing thing, Allen said, was that his mother ran out and bought one.

Sunday’s San Jose Mercury had a front-page article (graphic shown) about the possibility of instituting a universal basic income to remedy the huge job loss predicted from automation. As usual, nobody promoting the idea has any suggestion of how the government would finance the trillions of dollars annually required. Perhaps a start would be to tax the robots, as suggested by Microsoft founder Bill Gates a few months ago.

Sunday’s San Jose Mercury had a front-page article (graphic shown) about the possibility of instituting a universal basic income to remedy the huge job loss predicted from automation. As usual, nobody promoting the idea has any suggestion of how the government would finance the trillions of dollars annually required. Perhaps a start would be to tax the robots, as suggested by Microsoft founder Bill Gates a few months ago.

Still, at least people are talking about the problem of the jobless automated future — that’s more than you can say for Washington which remains on full snooze mode.

But nobody is discussing how robots taking millions of jobs in the near future eliminates the need to import additional immigrant workers. Instead, open borders hacks like Senators John Cornyn and Ron Johnson are pitching increased immigration of 500,000 workers annually to replace citizens.

As usual, Washington is headed in the wrong direction.

]]>Do nothing, get cash? Maybe, when robots take your job, San Jose Mercury News, May 22, 2017

With an impending robot revolution expected to leave a trail of unemployment in its wake, some Silicon Valley tech leaders think they have a remedy to a future with fewer jobs — free money for all.

It’s called universal basic income, a radical concept that’s picking up steam as a way to provide all Americans with a minimum level of economic security. The idea is expensive and controversial — it guarantees cash for everyone, regardless of income level or employment status. But prominent tech leaders from Tesla CEO Elon Musk to Sam Altman, president of Mountain View-based startup accelerator Y Combinator, are proponents.

“We should make it so no one is worried about how they’re going to pay for a place to live, no one has to worry about how they’re going to have enough to eat,” Altman said in a recent speech at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. “Just give people enough money to have a reasonable quality of life.”

Altman is personally funding a basic income experiment in Oakland as the concept gains momentum in the Bay Area. Policy experts, economists, tech leaders and others convened in San Francisco last month for a workshop on the topic organized by the Economic Security Project, co-founded by Altman. The project is investing $10 million in basic income projects over the next two years. Stanford University also has created a Basic Income Lab to study the idea, and the San Francisco city treasurer’s office has said it’s designing pilot tests — though the department told this news organization it has no updates on the status of that project.

Proponents say the utopian approach could offer relief to workers in Silicon Valley and beyond who may soon find their jobs threatened by robots as artificial intelligence keeps getting smarter. Even before the robots take over, some economists say basic income should be used as a tool to combat poverty. In the Bay Area — where the rapid expansion of high-paying tech companies has made the region too pricey for many to afford — it could help lift up those that the boom has left behind.

Unlike traditional aid programs, recipients of a universal basic income wouldn’t need to prove anything — not their income level, employment status, disability or family obligations — before collecting their cash payment.

“It’s a right of citizenship,” said Karl Widerquist, a basic income expert and associate professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar, “so we’re not judging people and we’re not putting them in this other category or (saying) ‘you’re the poor.’ And I think this is exciting people right now because the other model hasn’t worked.”

That means a mother living on the poverty line would get the same amount of free cash as Mark Zuckerberg, Widerquist said. But Zuckerberg’s taxes would go up, canceling out his basic income payment.

The problem is that giving all Americans a $10,000 annual income would cost upwards of $3 trillion a year — more than three-fourths of the federal budget, said Bob Greenstein, president of Washington, D.C.-based Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. Some proponents advocate funding the move by cutting programs like food stamps and Medicaid. But that approach would take money set aside for low-income families and redistribute it upward, exacerbating poverty and inequality, Greenstein said.

Still, some researchers are testing the idea with small basic income experiments targeting certain neighborhoods and socio-economic groups.

Y Combinator — the accelerator known for launching Airbnb and Instacart — is giving 100 randomly selected Oakland families unconditional cash payments of about $1,500 a month. Altman, who is footing most of the bill himself, says society needs to consider basic income to support Americans who lose their jobs to robots and artificial intelligence. The idea, he said at the Commonwealth Club, tackles the question not enough people are asking: “What do we as the tech industry do to solve the problem that we’re helping to create?”

Increased use of robots and AI will lead to a net loss of 9.8 million jobs by 2027 — or 7 percent of U.S. positions, according to a study Forrester research firm released last month. Already, the signs are everywhere. Autonomous cars and trucks threaten driving jobs, automated factories require fewer human workers, and artificial intelligence is taking over aspects of legal work and other white-collar jobs.

Meanwhile, the cost of goods and services in the Bay Area soared 27 percent over the past 10 years, and the median price of a home last year hit $880,000 — which fewer than 40 percent of first-time home buyers can afford, according to the 2017 Silicon Valley Index published by Joint Venture Silicon Valley. The price of renting a home has skyrocketed in recent years as well.

Proponents of universal basic income have varying ideas of how much money should be doled out to give people a decent quality of life. Clearly $1,500 a month isn’t enough in the Bay Area, but Altman says in a world of robots the cost of living would go down — some experts predict automation would lower production costs. In the meantime, an extra $1,500 still could have a big impact for Oakland residents like 32-year-old Shoshanna Howard, who says the salary she makes working at a nonprofit barely covers her cost of living.

“I would pay off my student loans,” she said. “And I would put whatever I could toward savings, because I’m currently not able to save for my future.”

Interest in basic income first spiked in the 1960s and 1970s, when small pilot studies were conducted in states including New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Iowa and Indiana, as well as Canada. Some studies showed improvements in participants’ physical and mental health, and found children performed better in school or stayed in school longer. But some also showed that people receiving a basic income were inclined to spend fewer hours working. Other data suggested married participants were more likely to get divorced — some experts say the cash payments reduced women’s financial dependence on their husbands.

Y Combinator has plans to expand its experiment to 1,000 families. YC researchers are using the small Oakland pilot to answer logistical questions — such as how to select participants, and how to pay them. The researchers have said they’re focusing on residents ages 21 through 40 whose household income doesn’t exceed the area median — about $55,000 in Oakland, according to the latest Census data. They expect to release plans for a larger study this summer.

Y Combinator announced its Oakland project last spring, but since then has kept many details under wraps. That tight-lipped approach concerns some community members who question whether the group did enough to involve Oakland residents and nonprofits.

Jennifer Lin, deputy director of the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy, said her organization reached out to YC about a year ago, but never heard back. “It makes me question what Y Combinator has to hide,” she said.

Lin is skeptical that basic income can do much lasting good in Oakland. What the city needs is more high-paying jobs and affordable housing, she said.

Elizabeth Rhodes, YC’s basic income research director, said the group is working with city, county and state officials, and has met with local non-profits and social service providers.

“We want to be as transparent as we can, but protecting the privacy and well-being of study participants is our first priority,” she wrote in an email.

Meanwhile, Rep. Ro Khanna, a Silicon Valley Democrat, is pushing for a plan that has been described as a first step toward universal basic income. Khanna this summer plans to introduce a long-shot $1 trillion expansion to the earned income tax credit that is already available to low-income families. But unlike a basic income, that money would go only to people who work.

“There’s a dignity to work,” Khanna said. “People, they don’t want a handout. They want to contribute to the economy.”

Testing universal basic income

Several groups are experimenting with unconditional cash payments. Here are a few examples:

Y Combinator is giving 100 randomly selected families in Oakland a basic income of about $1,500 a month, and expects to reveal plans for a larger study this summer.

Non-profit GiveDirectly is raising money to launch a basic income study in Kenya. The group plans to give cash to more than 26,000 people, some of whom will continue to receive payments for 12 years.

Finland in January began giving 2,000 citizens a monthly income of almost $600 as part of a study set to last two years.